This Election Day, Not Peace, but Division

On the theological meaning of today’s political environment

Each day, texts and calls.

Go vote.

Do you have a plan to vote?

Kamala Harris needs you to vote.

Donald Trump has a personal message for you.

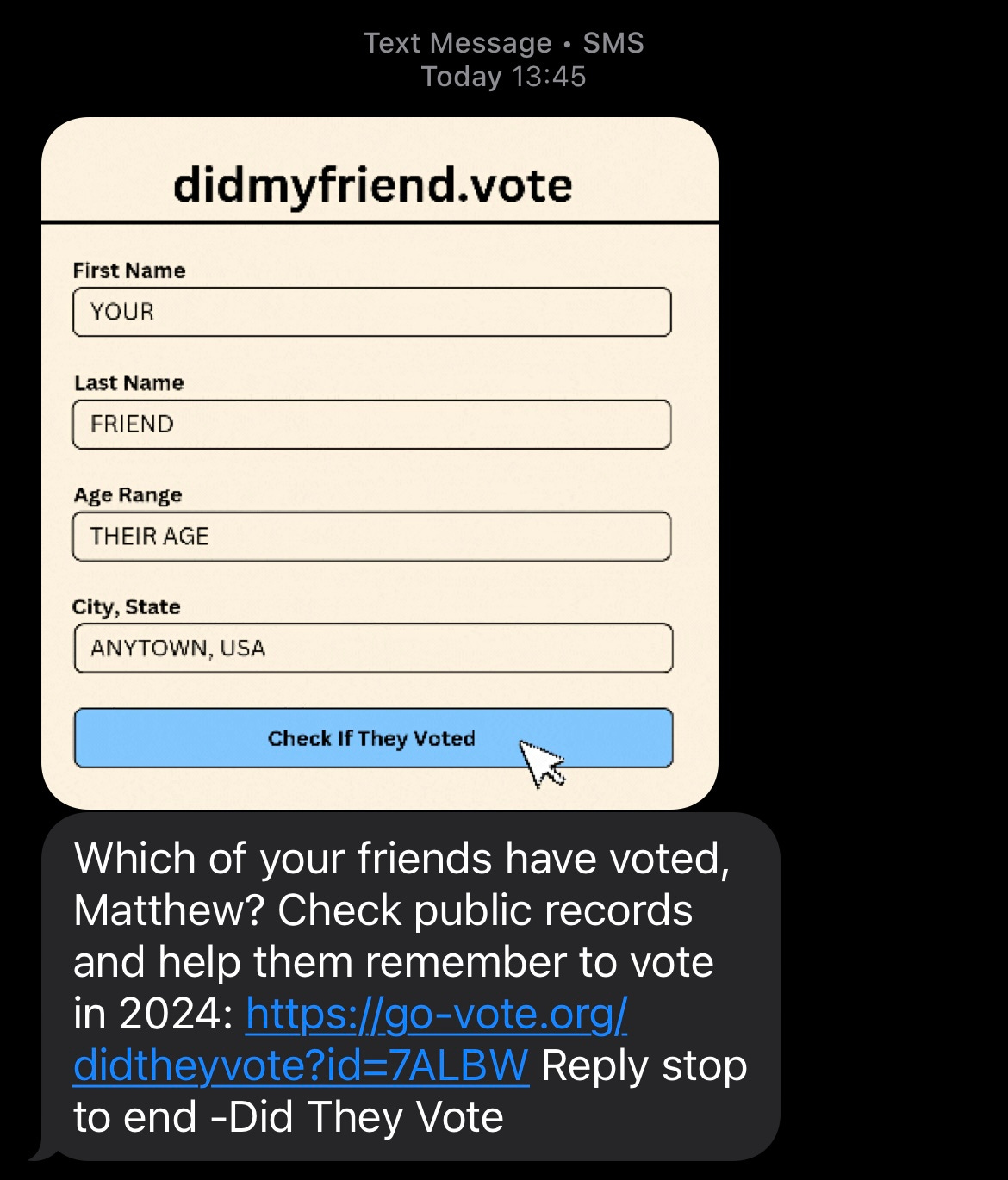

A few days ago, someone from a local Democratic campaign stopped by the house. At the end of her spiel, her parting words were delivered with ominous cheer: “Now remember, who you vote for is private, but whether or not you vote is a matter of public record!” The following day, I received this text message:

Like Vaclav Havel’s greengrocer, who felt pressured to put a sign in the shop window saying, “Workers of the world unite,” the true message is clear. It is intimidation. It is a reminder that you, the recipient, are being watched, that the society in which you live will not hesitate to discipline you with ostracism, that you know what you must do if you wish to be left alone.

Such messages provide a striking and clear picture of our culture at present. No sphere of life is to be respected as non- or pre-political. Your friendships and relationships with neighbors must now endure ideological screening; yard signs are a kind of political “TSA PreCheck,” signaling in advance that one is a safe fellow traveler. Your neighbors need to know what sort of person you are: do you support the right causes and oppose the wrong ones? Are you voting in accordance with the requirements of your skin color, sex, gender identity, sexual desires, and fertility? Do you understand that these characteristics obligate you to cast your vote freely for a candidate that has been pre-selected for you?

Interest groups and demographic blocs are nothing new, but discarding the aspiration of universal justice is. At its best, identity politics is an effort to meet the needs of an interest group within the larger effort of pursuing justice for all. But just as journalists took the impossibility of total objectivity as a license to turn every news story into an editorial, citizens too have taken the impossibility of universal justice as license to pursue raw power for their identity groups. This shift turned every identity into both a weapon and an invitation to mistreatment. Still not sure who to vote for? “You ain’t black.” Not sure about Kamala Harris? You’re a problematic white woman. Supporting the wrong candidate? You’re a race traitor.

This dynamic has played out explicitly with media fawning over Tim Walz: sure, they conceded, he’s a white man and he served in the military and he coached football, but he’s a paragon of “positive masculinity.” And as a positively masculine man, Walz and all other non-toxic men know that they have a duty to the women in their lives to vote as these women would want them to vote—like reparations a husband can pay to his wife and daughters for the centuries of patriarchy and, no doubt, resulting intergenerational trauma they have inherited. Walz is an exemplary penitent, forever sorry about his penis and pale skin.

No one is unaffected by life in this sort of political environment. If the most fundamental, immutable facts about a person, such as race and sex, are so politically significant, then everything else in a person’s life must be political too. And that means your intimate relationships. Love is made politically conditional. One is expected not to befriend a person with different political opinions, and to exercise great caution if you must spend time with one: we have developed ideological hygiene practices to avoid contamination or emotional disturbance. Ending a friendship over political differences is totally justified—and very, very brave.

And, of course, one is always permitted to take time away from family.

This permission to be excused from obligations to family bonds because of politics is the most noxious aspect of the political environment. To state the obvious: family members are natural obligations, commanding under normal circumstances our most rigorous allegiance. These relationships, more than any other, entail mutual dependence for survival and thriving. I presume this is why in almost every culture except this one, it is unquestionably dishonorable to disavow one’s family.

“But,” my imaginary interlocutor will interject, “this is exactly what you criticized! Are not all black people in a white society family? Are not all women sisters? Are they not obligated to one another in their politics?”

And to my conversation partner, I say: you’re right, but not in the way you think. Because, in fact, while biological family commands our natural loyalty, these family relations are not absolute. The question is: what may rightfully relativize those relationships—what has a rightful claim on us that takes priority over familial bonds, that may tell us who our true family is and what does not count as family?

We are confronted with the fact of religion. What we are always attempting to do with religion is, in the theologian Paul Tillich’s words, to set before ourselves that which is “ultimate” and deserving of our “ultimate concern,” in relation to which everything else is relative, provisional, and of penultimate concern. And apart from those religious traditions that collapse ultimate concern into family loyalty or sacralize the family, as with ancestor worship, religion is what sets the limit on family obligations. God defines for us what true family is and who may free us from family. Indeed, we might say that “whoever has authority to create or uncreate family” is a good everyday definition of the word “God.”

In light of such a definition, we might even say that Jesus’ most troubling statement in the Gospels is in fact his way of identifying himself as the true God who has come in the flesh: “Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division! From now on five in one household will be divided, three against two and two against three; they will be divided: father against son and son against father, mother against daughter and daughter against mother, mother-in-law against her daughter-in-law and daughter-in-law against mother-in-law.”

Or, in reverse: if Jesus isn’t God in the flesh, then such a statement reveals that Christianity is a demonic force, exactly as Tillich means the word—as a relative thing claiming to be absolute, a penultimate thing demanding our ultimate concern. In other words, idolatry. The person under the spell of idols is afflicted by devils who intend only his or her destruction. Compelling people to destroy family bonds in the name of politics achieves just that.

And this takes us back to our political environment. That our political leaders encourage us to engage in a little neighborly surveillance, that they herd us into voting blocs determined by immutable traits, that they insinuate themselves into our intimate relationships and assert the right to set us against our families—all this is their way of saying that they are not politicians but priests serving a terrible god. The toxicity of our political environment is no accident: this is just what it is to be in the grip of demonic forces.

What is needed, then, is an exorcism, and that means the solution to our politics is not a political solution. Voting for the right or the wrong candidate will not change the situation: the devil is happily bipartisan, so long as politics is our idol. No, what is needed is fundamentally and thoroughly spiritual. Only when we can say with the prophet Isaiah that “the nations are like a drop from a bucket, and are accounted as dust on the scales,” that is, only when we can see against the horizon of the ultimate how small are our worries, will these relative, penultimate things like politics be set right and take on their true meaning in our lives.

Such a thoughtful essay.

This was brilliant Matthew:

"This dynamic has played out explicitly with media fawning over Tim Walz: sure, they conceded, he’s a white man and he served in the military and he coached football, but he’s a paragon of “positive masculinity.” And as a positively masculine man, Walz and all other non-toxic men know that they have a duty to the women in their lives to vote as these women would want them to vote—like reparations a husband can pay to his wife and daughters for the centuries of patriarchy and, no doubt, resulting intergenerational trauma they have inherited. Walz is an exemplary penitent, forever sorry about his penis and pale skin."

As I put in a Substack note, the one social theoretical view that truly dominates our collective unconscious, our "social imaginary" is still feminism. Race and class are all downstream from the gender identity battle and the "virtues" and "vices" that it produces and propagates. This is endemic in our political world, our entertainment world, and in our churches as well.