Is the Church Obsolete?

Some thoughts on church decline and the Christian fantasy of relevance

With increasing regularity, we receive updates about the state of the church in America—that it is in decline. We were recently directed to notice that Gen Z males are more likely to be church affiliated than their female counterparts, and the accompanying commentary generally made the case that men are becoming more conservative, while women are finally walking away from a longstanding stronghold of patriarchal values. Then, a few days later, The New York Times published an article about the difficulty that black churches face trying to recruit and retain younger members. The reason this trend is said to matter is that the decline of the Black Church means a loss of a context that generated progressive activism, rallying for the Democratic Party, and future Democratic Party leaders.

I find both trends quite disturbing, but I must confess that what stands out to me most is the absence of any truly compelling reason for Gen Z women or young African Americans to participate in the church’s life. In most of the commentary I have seen, the religious affiliation of these groups is seen either as an epiphenomenon—“Men benefit from social and political conservatism, and so they are gravitating towards Christianity”—or as an instrument for some other, higher purpose—“The decline of the Black Church decentralizes black political power.” What the church is actually for? Few seem to remember.

In the past, I have asked friends, ministry colleagues, and church people if they believed people outside of the church lacked anything vital. “Does the pagan need what the church is offering?” As you’d expect, answers varied and the more theologically progressive Christians were far less willing to say that people who didn’t believe in Jesus needed to.

Of course, Christians are not a different species than other humans. If one can say, “My Muslim neighbors are, without Jesus and his church, in a perfectly satisfactory relationship with God,” then one is necessarily also saying about oneself, “The role played by Jesus and his church in my relationship with God could be played by someone or something else: they are replaceable.”

In my head I can hear my more progressive friends objecting that, no, they could never let go of Jesus. But we’re not talking about their feelings of attachment to him, are we? Jesus and the church may be very dear to these people, he may hold immense sentimental value and may be the embodiment of their highest moral and spiritual ideals, but nevertheless, strictly speaking, the theological reasoning is unavoidable: if Jesus isn’t needed by everyone, he isn’t needed by anyone. He may be chosen and even cherished, but he is not indispensable.

The same logic applies to whole communities. Churches are not immune to the implicit belief in Jesus’ dispensability. In the last few years, there has been no shortage of political commentary—much of which I agree with—that has argued that Christianity is needed for Western civilization and its guiding principles to survive. Famously, the essay in which the writer and activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali spoke about her conversion—the authenticity of which I do not doubt —focused on the role that Christianity plays in Western civilization. But one should be clear-eyed about this matter. If the point of Christianity is the survival of the West, then Christianity may be treated as a useful fiction or a necessary evil alongside things like police forces and the military. The place of Jesus in such a Christianity is clear: he is a mascot, a long-dead victim of Roman imperialism and religious zealotry whom we invoke when we need a symbol, so that we may display him for all to see, pinned to the cross by our highest values and current political aspirations.

The outcome is not a secret. The churches that live as though Jesus is optional have been, despite their best verbal efforts, saying effectively and forcefully to their members and to the world that what the church uniquely has to offer is not needed, and that the church is here to serve those realities which already exist beyond the church’s baptismal boundaries.

In my own context, this dynamic takes the acute shape of church attempting to play the role of unasked-for chaplain to progressive cultural and political movements: for example, Episcopal churches regularly participate in local Pride parades, as though LBGTQ+ individuals are begging for our acceptance, as though they have searched and searched in vain for a church to welcome them in. My point here isn’t the merit or lack of merit of LGBTQ+ acceptance; more basically, it is the absurdity of gestures like performing acceptance to people who are gathered to announce that they have accepted themselves, so that the end result is a church offering to give people what they already have—covertly asking them to accept us, to keep our church alive and relevant, long past our expiration date.

It will not suffice to say that the ethic of unconditional acceptance originated in Christianity, even though I agree that it did. The church gave birth to a culture that successfully extracted from Christianity moral goods, leaving behind the metaphysical and “mythological” baggage that helped define these secularized Christian values: universal equality, universal rights, acceptance of minorities, religious liberty, concern for the weak, the marginal, and the oppressed, and a host of other genuinely good things.

A church that holds up secularized Christian values as the point of the Christian faith is not a church worth attending—let alone giving money to. So I have great sympathy for those who have stopped going to church or who haven’t bothered to try it. Theologically, I am one of those people who believes that every person needs Jesus—that a person lacks true life without him. But the evidence is in: the people have stopped going, and at the risk of saying the obvious, they have concluded they don’t need to go. They’re not getting anything out of church that they don’t already have. Who can blame them for quitting?

I have become convinced that one of the primary challenges for Christians today is to come to terms with the overwhelming success of secularized Christianity. It is a great comfort to a Christian to say to himself or herself that secularized faith doesn’t actually work: it is how we tell ourselves that secularism will collapse under its own weight and that we’ll be here waiting when it happens, ready to welcome the world back into our arms. But of course, this is a fantasy about our own relevance. We are the secular culture’s ex-girlfriend, and telling ourselves that the new girlfriend isn’t pretty and that the culture will eventually see that it needs us is a pathetic expression of our need, not the world’s.

Conveniently, the Christian has little stake in the success of Christianity, what Karl Barth sometimes called the Christian religion. It may even be that the crisis we face in the widespread rejection of the Christian religion is a doorway into rediscovering what Jesus alone has to offer. Perhaps the wildly successful project of Western modernity is Jesus’ way of saying to his church that he does not need us to exercise his lordship of the world, and that it is him the world needs and not us. Perhaps we should celebrate that the world has received these goods from Christianity, and rejoice that we still have our greatest gift to give. Perhaps the best way for the church to be of service to the world and to Western society is to risk our own irrelevance by being about our own life and the message the Lord has given us. Perhaps!

the point about disposibility is exactly right, churches that are growing and have a future are exclusivists about christianity. the point about coming to grips with the success is out of touch particularly with gen z. its the success of capitalism, materialism, therapeutic religion but not a form of christianity.

A great read. Also, if the end goal of Jesus-followers is getting people to 'come to church' or 'dominating the culture', the battle is already lost. I don't go to church because that's what it means to be a Christian, I go to church because in knowing Jesus I realise I am drawn to be part of His body, made up of other Jesus-followers. So the knowing of and dedication to Jesus is the root and the church attendance is (one of) the fruit(s).

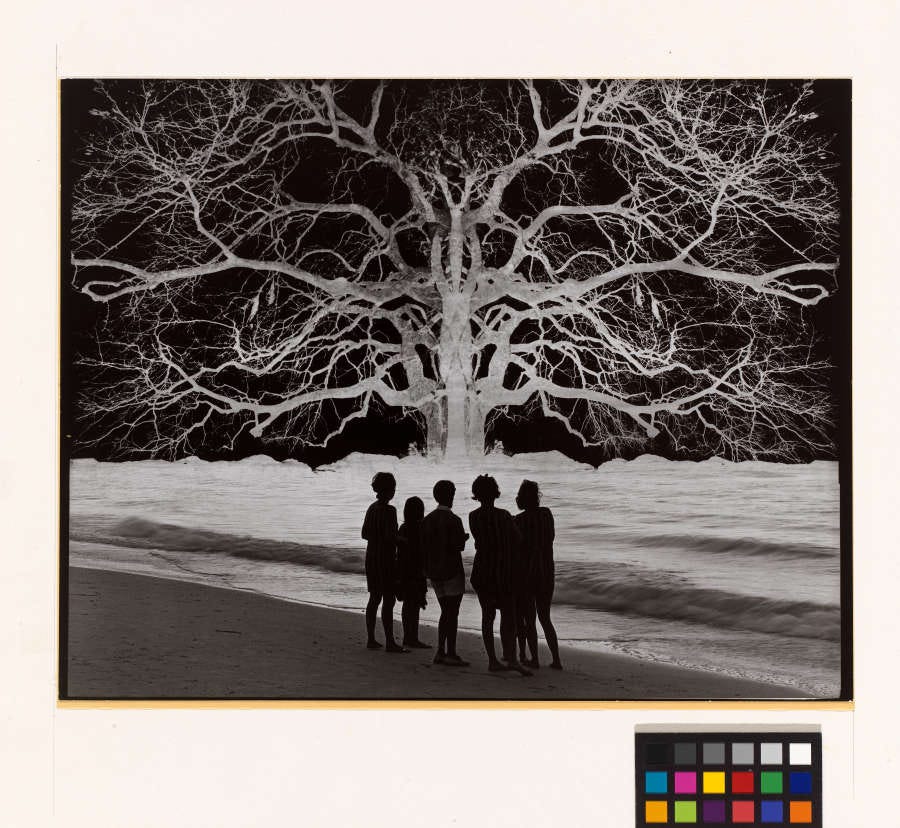

Actually, in writing the above I think the root vs fruit paradigm is actually a great way to analyse a lot of what you are writing about here. We are mostly distracted with outer things which are visible, but that's love trying to heal a sick tree by tending to its flowers and fruits, not looking at the health of its roots and what source they are drawing water from.