A reminder that only God is God

Why theology of culture must contradict itself to be of any use

It’s right there in the name, “theology of culture.” Theology is meant to be reasoned discourse about God, but there’s this little preposition, “of.”

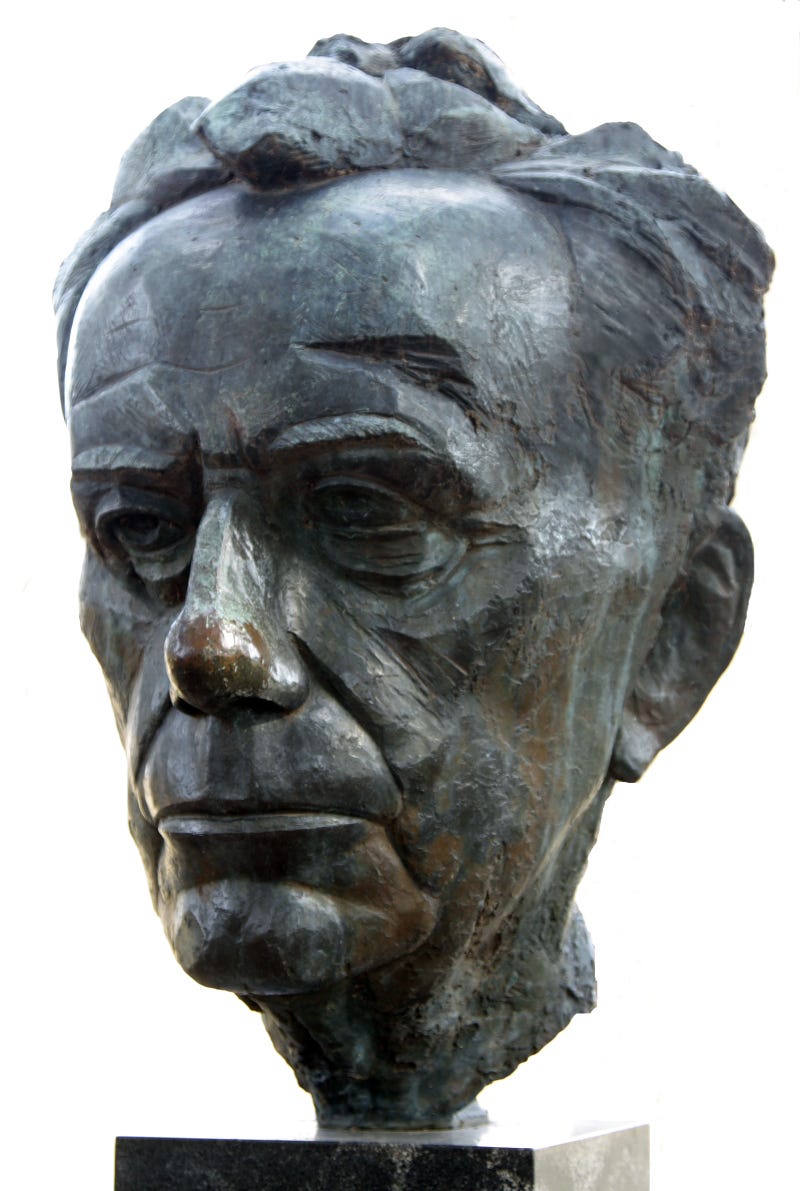

It’s easy not to think much of it, but that little word means something: it means letting culture have a say in what gets said about God. Worse than that: while “God,” to use the language of Paul Tillich—the theologian of culture—is that which concerns us ultimately, the Unconditioned, theology of culture is devoted to what is conditioned, i.e., culture. Theology of culture is about what theology says to culture, how theological ideas can shape or challenge or make sense of a culture. It claims to be theology, but culture is its point.

That is: theology of culture falls into a performative contradiction. In practice, it treats the culture as the ultimate concern, putting theology in the service of culture or politics. It inadvertently treats God as a means to a cultural end.

But the creation—including human cultures—exists for God’s pleasure. Our culture is a means of service to God. And the living God is never “for” anything: God has no purpose higher than himself to fulfill; his existence is not in the service of something else. A Christian theologian of culture has to contradict the performative contradiction. One must make theological sense of the culture, attempt to discern what the gospel says to the culture, and then repent of the inadvertent but inevitable idolatry.

It has long been my conviction that Christian churches in America have failed at that final step. As a non-evangelical and non-Catholic, I try not to comment too much on evangelicals and Catholics, but it’s hard not to point to the displays of Christian piety at the recent Republican National Convention as a practical example of what I’m talking about. Contrary to a lot of handwringing about Christian nationalism (which seems always to imply that Christians need to leave their moral convictions at home and that faith has no place in public debate), the real problem with Christian nationalism is that it wields Christianity as a means to a national end, and it neglects this final step of repenting for putting God in the service of the culture. The Christian nationalists are right that there’s no total separation of religion from the state; their mistake is to think that Jesus can be put in the service of America’s “greatness.” And make no mistake: liberal Protestant Christians are doing the exact same thing, only we don’t call it Christian nationalism because the agenda is morally progressive. The point: it’s not a conservative or progressive thing, nor a religious or secular thing. It’s a means and ends thing.

Theology of culture is doing its job when it reminds us that God is our true end and that the culture is therefore not our end.

Tillich contrasts “ultimate” concern with those concerns that are “conditional” and “preliminary”: things that matter only relatively, and only matter up to a point—they are confined to life prior to the “limin,” the threshold that stands between this life and the ultimate. I have my disagreements with Tillich, but he’s correct on this issue. Being a person with faith—in Tillich-ese, being “ultimately concerned”—is synonymous with freedom. “Freedom is nothing more than the possibility of centered personal acts…. In this respect freedom and faith are identical,” he writes. But this is only true as long as what claims our unconditional concern is actually the Unconditional. If our ultimate concern is directed to what is preliminary, if we are unconditionally concerned about conditional things, we are not free.

And that is the paradox of the Christian situation in the culture. The greatest gift a Christian can give the culture is to live in relative freedom from the culture, to remind people that the culture is conditional and preliminary, that there are higher concerns. It doesn’t mean that preliminary concerns don’t matter; they just don’t matter absolutely.

I’ve been thinking about this, of course, in relation to American politics right now. Like everyone, I’m compulsively checking the news. It also seems I may have been mistaken in comparing Joe Biden’s stubbornness to the hardness of Pharaoh’s heart. Almost immediately after reading about his departure from the presidential race, I was filled with compassion for him: every last one of us is a victim of our own foolish pride, but awfully few of us have this story play out in front of the whole world, suffering not only self-betrayal but also public humiliation. His tragedy is everyone’s tragedy. He’s just one of us—a human. I pray for him, especially as he enters a dark and disorienting chapter of his life as a consequence of his decisions, that God will give him freedom from all of us, which is to say, the peace of faith.

I’m susceptible to the temptation to respond to the news cycle with theology: the temptation to treat the culture as an end. I’ve been thinking about that temptation a lot, and trying to resist it. What I’ve written here is, in that sense, mostly for me; a reminder not to put theology in the service of The Discourse. I believe God speaks to our world by the gospel of Jesus, and I wonder if one of the ways the Lord may speak to American culture today is in the form of faithful dispassion—perhaps even silence. What good, hard news is it Christians might deliver to the world: The culture isn’t an end. It is just another creature. You’re just creatures.

"Faithful dispassion" may be reasonable (or urgently needed) for these large, consumeristic/entertainment-driven news cycles, but I fear the call towards detachment could exacerbate certain areas of cultural neglect, especially the care for local land and communities. We must always be on guard from idolatry, and presidential elections are particularly fertile ground for our idolatrous hearts, but a general call towards cultural dispassion might just support the comfort and laziness of middle-ground Christians already detached from the culture-war and detached from the responsibilities we have to our local communities.

For example, my neighborhood has recently received news of two polluters shutting down this summer, which makes the air less toxic for the toddlers in the daycare across the street. Even if this great victory over pollution didn't happen, yes, God would still be God, and my life and worship would go on, but also my cultural work of seeking justice. In the words of Matthew 12/Isaiah 42, I am aspiring to "not quarrel... in the streets", but to (passionately) help bring "justice through to victory" within my small circle of influence.

I like that—faithful dispassion. Or, practicing the virtue of detachment/non-attachment